It is a truth universally acknowledged that choking isn’t great.

None of these stock image people are having a good time choking.

We’ve seen it in movies, we’ve read about it in books, and we might have even seen it in real life. It’s dinner time and someone stops talking mid-chew. Desperate and turning blue, they grasp at their neck as if there’s something stuck. They’re choking.

Choking is the fourth leading cause of unintentional injury death. It’s a deadly problem, a familiar phenomenon, and something uniquely human. Humans are more susceptible to choking than other animals, and are the only known species to be able to choke on their own food.

How does choking happen, when did choking evolve, and why on earth are we humans choking on our food?

The Human Condition: Anatomy of Choking

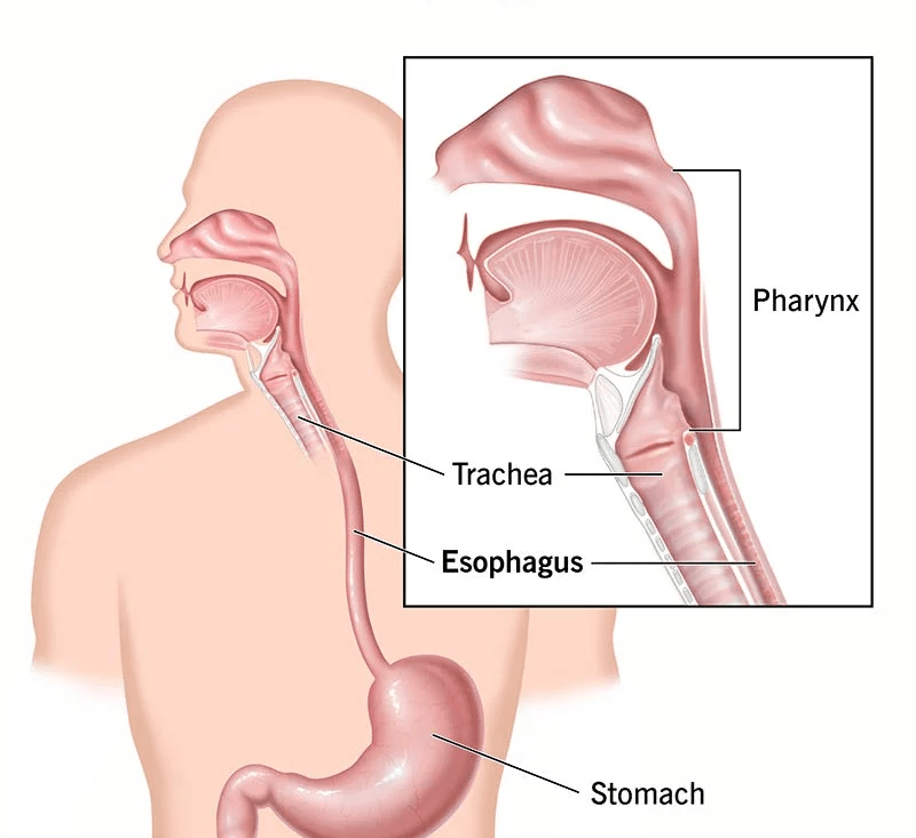

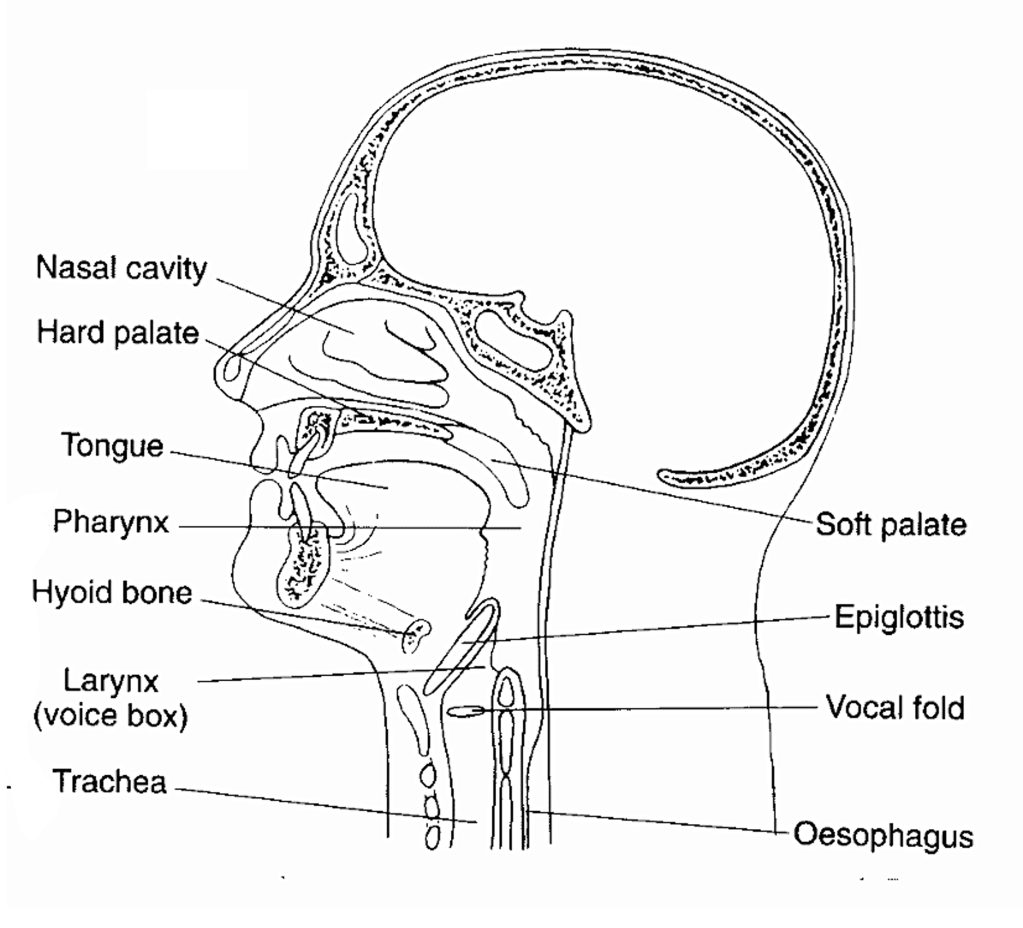

The human airways and food pathways are extremely close to each other. Air from the nasal passages or from the oral cavity passes through the pharynx into the trachea and down into the lungs. Food from the oral cavity passes through that same pharynx down into the esophagus and through to the stomach. When humans choke, food meant to pass through the esophagus instead get lodged in the trachea constricting air flow and potentially killing them.

Typically, the solution to preventing choking is the epiglottis. When swallowing, the flexible epiglottis bends in order to cover and block access to the trachea. The epiglottis in humans has an uphill battle in the fight against choking compared to other mammals, and thus it can fail. In order to understand why, let’s start by comparing the anatomy of a chimpanzee and a human.

The Descent of the trachea: Evolution of Choking

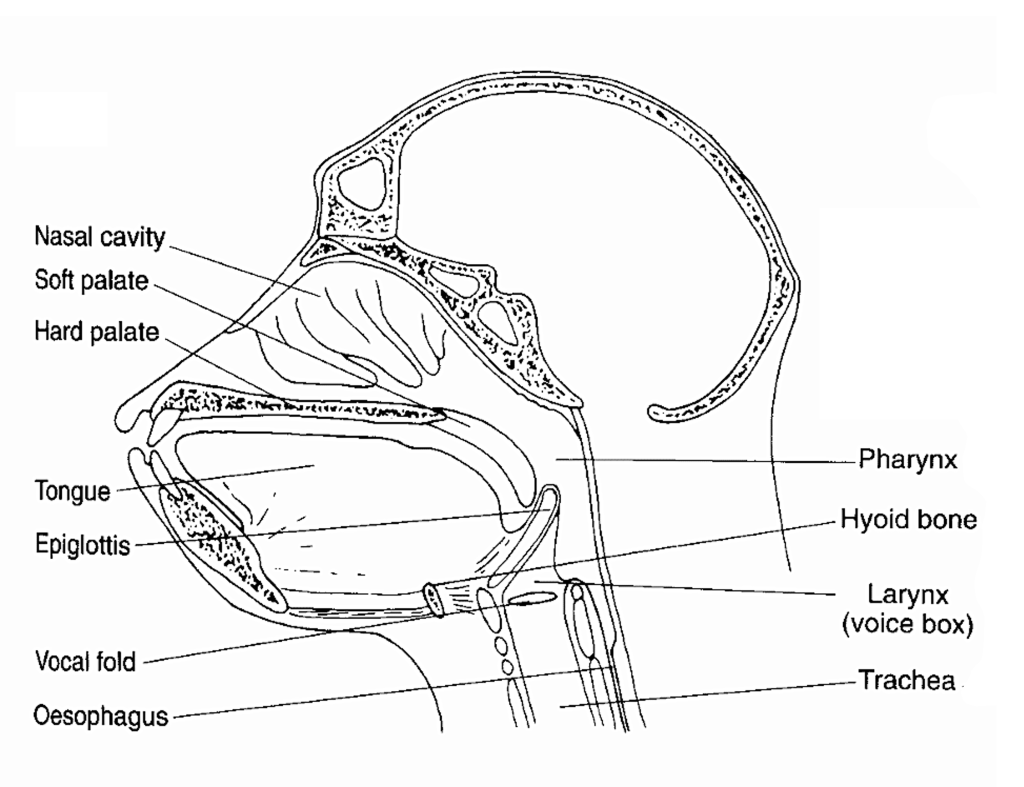

Compared to chimpanzees, two major differences float to the surface. First, the chimpanzee jaw juts out compared to the human. Second, because of how low the trachea is in humans, the pharynx in the human is proportionately much longer than that of the chimpanzee’s. Together, the short pharynx and jutted out face allow the chimpanzee epiglottis a greater margin of error than a human’s epiglottis.

Looking at our ancestors, we can see when we started evolving these traits that hurt us. Comparing with one of our more recent relatives, the Neanderthals, we can see they share more similarities with chimpanzee upper airway structure than they do with modern humans. An interesting wrinkle is that human babies also look more similar to chimpanzees and Neanderthals than they do to adult humans.

Humans are truly the oddballs. What is so important about choking that we gained the ability to do it where others, even our close relatives, even our infants, happily did not? What could be the function of choking?

Function of Choking

Spoiler Alert: Choking isn’t functional at all! But, it is a byproduct of what we’re actually after…

The Descent of the Trachea pt II: Evolution of Human Speech

The descent of the trachea and the shortening of the jaw give us something major: more room to work with in the pharynx. That extra room, and the closeness of the tongue to the back of the throat, allows humans to manipulate the shape of that space to make very important sounds to human speech- vowels.

The vowel sounds, /i/, /a/, and /u/, are found in every human language on Earth. They are vital to human speech. Revisiting Neanderthals, it is evident that their pharynx is not long enough to produce these deeper vowel sounds. It’s hypothesized that Neanderthal speech was higher pitched than human speech because of their shorter pharynx. It wasn’t likely they could reach these low vowel sounds.

When trying to figure out how this longer pharynx came to be, researchers compared the DNA of chimpanzees, Denisovans, and Neanderthals to that of humans (and their ancient modern ancestors) to suss out differences in the genetics that control the structures of the upper airways.

What was found was an enormous amount of methylation in humans and ancient modern humans. Methylation is when methyl groups (CH3) are added to the nucleotides in DNA. These methyl groups regulate the expression of genes by recruiting proteins or hampering transcription. In humans, there was methylation in face and voice associated genes. The skeletal genes associated with lower and mid facial protrusion and genes associated with the voice were rife with methylations, even though these categories of genes only account for 1-3% of the total genome, respectively.

Ancient modern humans seem to be the first to start the evolution towards speech as we know it by down regulating skeletal development genes via DNA methylation.

Revisiting Choking: The Tradeoff

Choking is a major risk for two subsets of the human population: young children and the elderly. Because of our anatomy, swallowing requires much more coordination than it does in other species. It’s a cognitively more demanding task!

Somewhere between 1 and 2 years of age, children will start to develop the long pharynx and shallow jaw associated with human speech. But before that, infants don’t struggle with choking. It is contested but often argued that infants are able to breath and swallow at the same time like other mammals can. If they can’t breathe and swallow at the same time, it is still safe to say that it is easier for them to coordinate breathing and swallowing because of their anatomy.

Coordination becomes an issue again with old age as cognition declines. In addition, elderly people chew less thoroughly as they lose their teeth and their ability to produce sufficient saliva, making food harder to swallow. Therefore, the likelihood that someone will get a food item lodged in their trachea increases with age.

In spite of these dangers, life as we know it would not be the same without human speech. Speech is a complex form of communication that, along with our advanced cognition, has allowed for a level of coordination we couldn’t otherwise achieve. Yes, choking on our own food is a significant hazard. Yes, it is silly to be the only species to struggle with choking. But, the benefit of speech seems a worthy tradeoff.

Figure 11. Gather with your loved ones around a fire. Look up at the stars and share a campfire story. Try not to choke on your smores.